Thursday 9 December 2010

Low-Level 'Adventures'

Reading this post on Discourse and Dragons, about relatively straightforward adventures that build up to a climactic battle against an archetypal monster, I was struck by how inappropriatethis adventure structure is for low-level characters. And I wondered how other DMs handle low-level adventures. What I mean is, D&D promises players that their characters will be heroes, but the first couple of levels – which if we go by a 3 game session per level rule of thumb, could be quite a long time – are spent worrying that a couple of goblin arrows will kill Hurkar the Strong, never mind imagining that Hurkar the Strong will hack his way through the goblin horde before doing heroic battle with the evil wizard, the bandit king, the Ogre chief… whatever. The low-level adventures that I run are either very short, practically single encounters with a few trailing threads to be explored, or exercises in rest and resupply. Neither of these capture the structure of heroic fiction.

The heroes stagger back to town, again.

Do people start their D&D characters at higher levels? Do they make judicious use of the DM screen to slide the characters though peripheral encounters to ensure that the session generates the sense of adventure and exploration? Or do they run combat-light adventures – the sort found in WFRP, which seems contrary to the spirit of D&D – that reward player characters for ‘sustainable’ adventuring?

Monday 6 December 2010

Flora, Fauna, and Fora

Okay, I'll return with a fairly light posting. It's been a busy time painting hills for my dwarfs shoot their cannons from, and then the dwarfs and cannons to put on those hills. And I paint slowly. Very slowly. So very slowly.

First, here is Head Injury Theatre's guide to the stupid monsters of D&D. D&D has lots of 'stupid' in it, but then D&D does consist of hundreds of books spread over 30 years. Some of these monsters are actually 'bad', in the way that lots of very early D&D was 'bad'. I don't want to have my players explore by routinely tapping the ground in front of them with a 12" pole because deadly traps are that commonplace. There's no heroism, adventure, or cleverness in that. It might remind us of the old days, and despite my fondness of old school RPG rule systems and game settings, the idea of dungeoneering being a series of escalating death-puzzles is about as exciting to me as D&D being World of Warcraft, now with added paper! I want my players to role-play their characters, be heroes (or villians, or snivelling sneaks) and have fun doing so. Which is why this is a bad monster.

It's not that it's stupid, it's that it's bad. Just how are a party of adventurers meant to cope with that. How will the players not feel that they've been 'cheated' when the ceiling drops down on them and kills them. Put The Lurker Above, and its kin, in your game, and you've got henchmen taking point once the players re-roll their characters. Heroes all.

Anyhow, I've been living my online gaming life around the Dragonsfoot (for all my classic D&D needs) and Bugman's Brewery (for my WFB Dwarfs) fora recently, and do recommend that if you interested in these game systems you check out those sites.

Labels:

DnD,

Dungeons and Dragons,

Dwarfs,

Monsters,

Stupid,

Warhammer Fantasy Battle,

WFB

Wednesday 22 September 2010

Lead Poisoning

No posts in a while… I’m not dead, but I am suffering from an acute case of lead poisoning. All I have done for the past few weeks is paint miniatures and play Warhammer Fantasy Battle.

My Dwarf army – the Dwarfs of the Kingless Halls, of Karak Angaz, the Industrious Hold, haven’t been performing that well in the field. In fact, the ineffectiveness of the Engineers’ Guild, with cannon balls falling short or bouncing long for the few rounds it takes for the Goblin Wolf Chariots to reach them, might well prompt a re-ordering of the power structure of the Hold. From syndicalist utopianism to military rule, perhaps?

This lead poisoning hasn’t just been eating my time, but also my imagination and my money. Right now I’m scouring eBay for the bits of an Empire mortar I need to build a Dwarf bombard (to be played ‘counts as’ a Grudgethrower). That’ll scatter those hordes of Greenskins!

Labels:

Dwarfs,

miniatures,

Warhammer Fantasy Battle,

WFB

Wednesday 18 August 2010

Never played D&D before? Never played a computer adventure game?

Then you will make a great role-player. Freed from the restrictions of understanding the mechanics and the constraints of game genre, you will take seriously the idea that this is a game is a product of the imagination.

Some time ago I ran a game of BECMI/Rules Cyclopedia D&D for my wife, my mother, and my teenage sister. We had created characters the day before, and I knew the game was going to be interesting from the amount of imagination they put into developing their heroic personas. By the end of character creation we had a ruthless veteran Thyatian warrior, a warrior priestess from the Northern Reaches, and a runaway teenage unlicensed magic user from Glantri.

I decided that we would play a version of module B9, Castle Caldwell. This is a short dungeon crawl with little to commend it apart from its simplicity. Which is exactly what I wanted from an adventure I would be using introduce three beginners to the game. In putting some meat on the bones, I had it that they would be hired by Cassius Capex, former slum landlord of Thyatis City in the process of turning his family into members of the respectable gentry. If he is successful, he will be able to serve as an early patron for the adventuring party. The first step in this process is the purchase of an abandoned fortified manor house and accompanying lands in northern Karameikos. Unfortunately, the abandoned manor is occupied and he needs some desperate/brave strongarms to clear his property. To add an NPC who could offer beginners tactical/game mechanic advice, I decided that Cassius will send his son, Atticus Capex to accompany the party and keep an eye on their efforts.

In hindsight, should I have done all this in a ‘cut-scene’? I have little aversion to using cut-scenes – extended periods of description that throw characters into an adventure or move the plot forwards between episodes of ‘open’ play. I use these to shamelessly ‘railroad’ characters into events, to place them at the doors of the dungeon, or knee-deep in intrigue (or in gore, depending on taste), before handing the characters over to the players. I see little wrong with this, as the idea that a GM is able to avoid ‘railroading’ is a nonsense - to give characters total freedom, after all, would involve beginning every game session with, ‘You wake up. What will Edwin the Bard do now?’ Or, like Tristram Shandy, we could try to begin with the conception of the characters. A good cut-scene can do away with that staple of adventure beginnings, ‘You spend the evening in the Skewered Boar. A strange man approaches you as you finish your Darokini wine’, and provide a beginning that is more cinematic, theatrical, or literary, depending on your tastes. For all that, the party met Cassius Capex in a tavern.

What followed was an excellent few hours of role-playing. The warriors and the runaway negotiated with Cassius, discussed his offer with each other, inspected the horses that he provided, weighed up Atticus as a party member, and generally failed to get on with the adventure. When they did arrive at Castle Capex they hid in the treeline and watched the entrance for the best part of a day, before watching a goblin hunting party return. They laid a plan to lure some goblins out, setting a smoky campfire to attract attention and concealing themselves some distance away. Four goblins were sent to investigate.

Dice rolling began in earnest. The party killed two, broke the morale of the remaining two and captured them. Under interrogation, the goblins told the party that their band controlled the castle, and ‘taxed’ the humans who used it. I wanted to offer the party hints that they might be able to clearing the castle largely by negotiation – the merchants, bandits, evil cleric, and goblins could all be persuaded to leave the castle when faced with swagger, threats, sharp blades and a little gold. The party would still have to fight the ravenous wolves, and whatever evil lurked in the cellars, but they would be able to role-play much of their way to success.

After the party put their prisoners to death – one of them was trying to escape, but I might have to look at an alignment shift for these Lawful heroes – I got my first sign that these players were so unfamiliar with adventure games of any description that they would need guidance. I needed to have Atticus get to his knees and search the bodies of the goblins in order to reward the characters with any treasure. And then, armed with information about the inhabitants of the castle the party rode back to town, Atticus grumbling all the way, to renegotiate with Cassius. They demanded that he hire a few more strongarms to accompany the party if they are to clear out a castle that is not only home to goblins, but also a couple of groups of ‘umans and that ‘strange chanting lady’.

A clever move in real life, perhaps. But not a gamers move. A gamer – even one only familiar with computer adventure games – would assume a difficulty scaling in keeping with the power of the characters. People with no familiarity with the way these games work see four novice adventurers, and a castle full of people and things who will try to stick pointy bits of metal into those people. Where a gamer might risk the life of his character to achieve progress in the game, and more importantly would understand the scale of these risks in terms of game mechanics, in this game the players – my wife, my mother and my teenage sister – used their imagination to assess the dangers of having fun storming the castle. They role-played their characters, and found that they were far more concerned with keeping their characters unharmed while earning enough money to escort the runaway novice magic user downriver to Specularum then they were achieving abstract character progress in the form of ‘levelling up’. Their lack of familiarity is what made the session such a fun role-playing experience, and such a frustrating adventure game.

Some time ago I ran a game of BECMI/Rules Cyclopedia D&D for my wife, my mother, and my teenage sister. We had created characters the day before, and I knew the game was going to be interesting from the amount of imagination they put into developing their heroic personas. By the end of character creation we had a ruthless veteran Thyatian warrior, a warrior priestess from the Northern Reaches, and a runaway teenage unlicensed magic user from Glantri.

I decided that we would play a version of module B9, Castle Caldwell. This is a short dungeon crawl with little to commend it apart from its simplicity. Which is exactly what I wanted from an adventure I would be using introduce three beginners to the game. In putting some meat on the bones, I had it that they would be hired by Cassius Capex, former slum landlord of Thyatis City in the process of turning his family into members of the respectable gentry. If he is successful, he will be able to serve as an early patron for the adventuring party. The first step in this process is the purchase of an abandoned fortified manor house and accompanying lands in northern Karameikos. Unfortunately, the abandoned manor is occupied and he needs some desperate/brave strongarms to clear his property. To add an NPC who could offer beginners tactical/game mechanic advice, I decided that Cassius will send his son, Atticus Capex to accompany the party and keep an eye on their efforts.

In hindsight, should I have done all this in a ‘cut-scene’? I have little aversion to using cut-scenes – extended periods of description that throw characters into an adventure or move the plot forwards between episodes of ‘open’ play. I use these to shamelessly ‘railroad’ characters into events, to place them at the doors of the dungeon, or knee-deep in intrigue (or in gore, depending on taste), before handing the characters over to the players. I see little wrong with this, as the idea that a GM is able to avoid ‘railroading’ is a nonsense - to give characters total freedom, after all, would involve beginning every game session with, ‘You wake up. What will Edwin the Bard do now?’ Or, like Tristram Shandy, we could try to begin with the conception of the characters. A good cut-scene can do away with that staple of adventure beginnings, ‘You spend the evening in the Skewered Boar. A strange man approaches you as you finish your Darokini wine’, and provide a beginning that is more cinematic, theatrical, or literary, depending on your tastes. For all that, the party met Cassius Capex in a tavern.

What followed was an excellent few hours of role-playing. The warriors and the runaway negotiated with Cassius, discussed his offer with each other, inspected the horses that he provided, weighed up Atticus as a party member, and generally failed to get on with the adventure. When they did arrive at Castle Capex they hid in the treeline and watched the entrance for the best part of a day, before watching a goblin hunting party return. They laid a plan to lure some goblins out, setting a smoky campfire to attract attention and concealing themselves some distance away. Four goblins were sent to investigate.

Dice rolling began in earnest. The party killed two, broke the morale of the remaining two and captured them. Under interrogation, the goblins told the party that their band controlled the castle, and ‘taxed’ the humans who used it. I wanted to offer the party hints that they might be able to clearing the castle largely by negotiation – the merchants, bandits, evil cleric, and goblins could all be persuaded to leave the castle when faced with swagger, threats, sharp blades and a little gold. The party would still have to fight the ravenous wolves, and whatever evil lurked in the cellars, but they would be able to role-play much of their way to success.

After the party put their prisoners to death – one of them was trying to escape, but I might have to look at an alignment shift for these Lawful heroes – I got my first sign that these players were so unfamiliar with adventure games of any description that they would need guidance. I needed to have Atticus get to his knees and search the bodies of the goblins in order to reward the characters with any treasure. And then, armed with information about the inhabitants of the castle the party rode back to town, Atticus grumbling all the way, to renegotiate with Cassius. They demanded that he hire a few more strongarms to accompany the party if they are to clear out a castle that is not only home to goblins, but also a couple of groups of ‘umans and that ‘strange chanting lady’.

A clever move in real life, perhaps. But not a gamers move. A gamer – even one only familiar with computer adventure games – would assume a difficulty scaling in keeping with the power of the characters. People with no familiarity with the way these games work see four novice adventurers, and a castle full of people and things who will try to stick pointy bits of metal into those people. Where a gamer might risk the life of his character to achieve progress in the game, and more importantly would understand the scale of these risks in terms of game mechanics, in this game the players – my wife, my mother and my teenage sister – used their imagination to assess the dangers of having fun storming the castle. They role-played their characters, and found that they were far more concerned with keeping their characters unharmed while earning enough money to escort the runaway novice magic user downriver to Specularum then they were achieving abstract character progress in the form of ‘levelling up’. Their lack of familiarity is what made the session such a fun role-playing experience, and such a frustrating adventure game.

Labels:

Castle Caldwell,

DnD,

Dungeons and Dragons,

Roleplaying

Wednesday 21 July 2010

Clever Player, Stupid Character?

Or the other way around.

Role-players are usually comfortable with the idea that the characters can be physically dissimilar to players. We do not blink when the character being played by a weakling bends iron bars or lifts boulders, or when the character played by a clutz nimbly disassembles a deadly trap, or when the player who is never completely well rolls up a character with a constitution of 18. The dissimilarity of the characters and the players is enforced by the way in which physical characteristics are bound into the mechanics of the game.

Characteristics such as wisdom, intelligence, and charisma – personality and cognitive characteristics – seem to present many role-players with a problem. They are often not tied so strongly into the mechanics of the game. They might determine how many spells you can learn or cast, or offer slight modifiers to reaction rolls, but their effects are not felt in the mundane mechanics of the average role-play session. Complicating this is the feeling that the activities that might be covered by these characteristics ought to be the proper domain of role-playing, not dice rolling. When a player says that his character will attempt to throw a goblin over a wall, a GM will ask the player to roll some dice. The GM will not ask for a demonstration. When a player says that his character will negotiate with a goblin, a GM will often ask the player to role-play this negotiation.

While Steve couldn't string two words together, never mind an argument, his character (Wis 17, Int 17, Chr 17) could speak like Cicero.

Role-players are usually comfortable with the idea that the characters can be physically dissimilar to players. We do not blink when the character being played by a weakling bends iron bars or lifts boulders, or when the character played by a clutz nimbly disassembles a deadly trap, or when the player who is never completely well rolls up a character with a constitution of 18. The dissimilarity of the characters and the players is enforced by the way in which physical characteristics are bound into the mechanics of the game.

Characteristics such as wisdom, intelligence, and charisma – personality and cognitive characteristics – seem to present many role-players with a problem. They are often not tied so strongly into the mechanics of the game. They might determine how many spells you can learn or cast, or offer slight modifiers to reaction rolls, but their effects are not felt in the mundane mechanics of the average role-play session. Complicating this is the feeling that the activities that might be covered by these characteristics ought to be the proper domain of role-playing, not dice rolling. When a player says that his character will attempt to throw a goblin over a wall, a GM will ask the player to roll some dice. The GM will not ask for a demonstration. When a player says that his character will negotiate with a goblin, a GM will often ask the player to role-play this negotiation.

While Steve couldn't string two words together, never mind an argument, his character (Wis 17, Int 17, Chr 17) could speak like Cicero.

I want to protect characteristics such as wisdom, intelligence, and charisma from being ‘stat dumps’ by giving them more mechanical prominence in a game. But I want to do this without cutting the role-play aspect of role-playing games. That said, a clever player, playing a D&D character with intelligence of 7, who solves puzzles, engages in complex negotiations, and the like, is no more playing a role-playing game than one who devolves everything to a characteristic test. A combination of characteristic tests and skill tests, modified GM judgement of intrinsic difficulty and role-playing decisions is the best way forward, I feel. A player might make an impassioned speech when negotiating with the King of the Assassins, but if the character who is to be making the speech has a low charisma score that might not be quite what comes out of the characters mouth. We would not consider for a moment that there should be one to one translation from player action/stated intention to character action when dealing with questions of physical action. This is not just to hobble the characters of the clever, charismatic players, but to boost the characters of players who are not so quick witted or charismatic. Just as a weakling can play a Herculean hero, so can the shy player who stumbles over his words play the greatest demagogue in the Known World.

Labels:

Characteristics,

DnD,

Dungeons and Dragons,

Roleplaying

Tuesday 6 July 2010

Standard Magical Items

In the real world, flags and standards are powerful items. A simple arrangement of symbols can evoke strong emotions; flags and standards can conjure pride, rally faltering courage, even generate fear. Some are sacred, and emotions generated when these flags are defiled points to the real power of these objects. And this is in a world where the only magic at work is the reification of abstract symbols by human cultures.

So why, in other worlds in which there are such things as magical symbols, in which heraldic banners flutter from every petty stronghold and trail from the lance of every knight errant, is there a paucity of magical flags?

In Warhammer Fantasy Battle (WFB), the power of flags is a standard (pun intended). Most units receive bonuses (magical and mundane) from the banners that they carry into the fight. But in Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), magical flags, banners, and standards are curiously rare. On US Independence Day, Dungeons and Digressions posted a list of some interesting magical flags that could be used in any fantasy role-playing game. I like the 'Flag of Allegiance' -

- not because it is unusual, or strange, but because it is essentially the real world power of a flag made magical and amplified.

"Stop looking at my chest, Top Hat, and defend the symbol of La Révolution!"

I am thinking of the use of magical flags to defend cities, to protect ships, to hearten Orc raiding bands... and the sort of role-playing encounters these items could enable.

Saturday 3 July 2010

Warhammer World Sportsnight

Blood Bowl is set in a Warhammer World. Not the grim world of Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play (WFRP), nor even the markedly lighter world of Warhammer Fantasy Battle (WFB). The world of Blood Bowl is violently silly. I do wonder what a game of WFRP set in this version of the Warhammer World would play like. There is enough background material in the various rulebooks, companion books, magazines, annuals, and even novels, to layer a Warhammer World devoted to the Cult of Nuffle over the grimdark world we already know. I would love to hear from anyone who has done this, whether for a one-off game or for a Blood Bowl-themed campaign.

When they said that their home ground was a fortress...

A few days ago, D retrieved his 3rd edition Blood Bowl (and Dungeonbowl) and we played a human v dwarf game. His human team sported their 15-20 year old paint jobs, while the dwarfs rumbled across the field flashing their bare lead. The first half was played without the four-minute per turn rule; it is a little difficult to play to that rule when you are consulting the rulebook on a more or less continuous basis. By half-time it was 1-0 to the humans, gifted a touchdown when their catchers broke the iron-wall of dwarven defence and we misinterpreted the mechanics of passing and catching. The second half was played with the four-minute per turn rule in effect, which made for a much more urgent, exciting, even tense playing experience. The game flowed - at least, the board game that D and I were playing flowed, the game of Blood Bowl that was being represented on the board was a static battle as the dwarf team ground its way upfield, eventually scoring a touchdown against the four remaining human players able to stand upright. Final score, 1-1, with the humans counting 2 dead, 2 seriously injured, and 4 knocked-out.

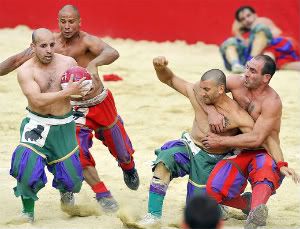

Blood Bowl Live? No, Calcio in Costume. "The modern version allows tactics such as head-butting, punching, elbowing, and choking, but forbids sucker punching and kicks to the head."

Miniatures, miniatures, miniatures. I have never used them when playing RPGs. I am not a great painter, never had the money to collect many, and given that the strength of using miniatures is in creating a vivid visual representation of the scenarios being described, I could not see the point in using a miniature to 'stand in' for some other monster or character. That the game takes place in the imagination is surely the very point of RPGs. Isn't it?

But miniatures, miniatures, miniatures. Before this game of Blood Bowl I had rescued by 1st edition Space Hulk from storage, and had made a start painting up a few genestealers in the classic blue/purple colour scheme. And while I am still not a great painter, I am a hell of a lot wealthier than I was when I was a teenager. So where does that take me? Straight past a fully-painted Blood Bowl team, a star player or two, and towards Warhammer Fantasy Battle, building a dwarf army, and some kind of Chinese hell in which tiny little plastic and lead men beg me to paint them to a standard that I can never achieve, and yet my disappointment only sharpens my appetite for more. And more.

A hell of a lot wealthier than when I was a teenager? Not for much longer.

Wednesday 23 June 2010

"What has thems gots for treasures?"

What sort of things do bandits, orc raiding bands, swooping wyverns, pixies, or any other 'monsters' have in their lairs? Just piles of coins into which the odd magic sword is stuck blade first? Hopefully not, though 'treasure as simple reward' does remind me of my early role-playing experiences. Kill, collect cash.

Ali Baba seems disappointed that the thieves' treasure horde included botany equipment, a flask of brandy, a big, dusty book, an old hammer, and a pair of very fancy leggings.

If you want a bit more colour, though, you could think about the kinds of items that these 'monsters' would accumulate. But if you are short of inspiration, there is always the internet. Via the Strike to Stun Facebook page, I have stumbled across Outworld Studio produced treasure generator. While has been written with Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play in mind, none of the items that I have used it to generate are so setting specific that they could not find a home in any fantasy setting. And if the items you generate are not to your taste, or do not fit the flavour of your campaign, just click again to re-roll.

Here is a typical output:

• A sturdy wooden box, about two feet by one foot by one foot, in which is kept a rattling collection of bottles, jars and phials. These contain a few dozen samples of seeds, leaves, flowers and berries, each in a preservative solution and carefully labelled. Also in the box are several pages of notes detailing where the specimens were found.

• A pewter flask engraved with a crossed hammer and chisel. It is full of brandy.

• A weighty tome titled 'Majestic Dynasties'.

• A pair of ermine trim leather leggings.

• A throwing hammer etched with a kill tally.

• A pewter flask engraved with a crossed hammer and chisel. It is full of brandy.

• A weighty tome titled 'Majestic Dynasties'.

• A pair of ermine trim leather leggings.

• A throwing hammer etched with a kill tally.

Thursday 17 June 2010

The Virtue of Alignment

Alignment systems in role-playing games are interesting things. They are often little more than a way of dividing the world into Goodies and Baddies, into White Hats and Black Hats. Sometimes they are a little more detailed, with a greater range of divisions, sub-divisions, and combinations, allowing them to serve as shorthand for characterization, offering simple role-play guidelines to players and GMs. And sometimes, they can tell you a lot about the ideas that underpin a whole game world.

But side-issues first; what on Oerth (or Mystara even) are alignment languages? I have never used alignment languages. The idea that characters and creatures of distinct species and distant cultures would be able to speak a non-learnable ‘secret’ ‘language’ by virtue of their ethical outlook seems ridiculous. More than that, it is an idea that makes keeping alignments secret impossible. ‘So, how to check whether this new recruit to our gang of slavers is really an infiltrator? I know – I will greet this new recruit in ‘Chaotic’. I would be grateful if anyone can think of a reason to use alignment languages – other than Gary says so – or can provide an example from a published adventure where alignment languages are used in an anyway interesting manner.

Back to the main discussion; both Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play (WFRP) and Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) use superficially similar alignment systems. These systems assign every intelligent creature in their fantasy universes to a category that summarises its moral outlook. And both the WFRP and D&D alignment systems use the juxtaposition of Law and Chaos as their central feature, appearing to have arrived at this moral cosmology by way of Michael Moorcock. D&D got there first, of course, and WFRP cannot be anything but influenced the use of a Law-Chaos alignment system in the daddy of all role-playing games. Nevertheless, it appears that it is WFRP that takes seriously the idea of a universe arranged around a conflict between Law and Chaos.

D&D has the more simple alignment system. Characters and monsters are Lawful, Neutral, or Chaotic. In the D&D Basic Set Players Manual (1983), alignment is discussed in detail on page 55. Putting Neutrality aside for a moment, a Lawful alignment is described as being about a belief in order, in following rules, in sacrificing individual freedoms to benefit the group. Chaotic is defined as ‘the opposite of law’, and is summarized as ‘the belief that life is random, and that chance and luck rule the world’. Chaotic characters are described as telling the truth or telling lies as it suits them, as acting on sudden whims, as having unpredictable behavior. So far so interesting. Those descriptions appear to fit nicely with a commonsense interpretation of what a Lawful or Chaotic person might be like. And yet, the final line of each summary is a statement that these alignments are usually the same as ‘good’ and ‘evil’.

The treatment of Law and Chaos as essentially the same thing as good and evil has never rung true for me. Not when I first played D&D, and not when I have returned to D&D after more than a decade without role-playing in earnest. But treating Law and Chaos synonyms for good and evil is exactly what most early D&D adventures did. This strips away the most interesting aspects of this alignment system. For as long as the D&D alignment system suggests that central moral distinction in the D&D world is not that of good vs evil but Law vs Chaos, we have the provocative idea that Sir Galant, a knight who lives by a strict code of chivalry, has significant similarities with the Magistrate Tyrant of Zagor. One good and one evil, perhaps, but both Lawful. By the time the D&D Cyclopedia (1991) was published, the claim for the idea that Chaos ≈ evil had been watered down, with a provision that ‘Each individual player must determine if his Chaotic character is closer to a mean, selfish “evil” personality or merely a happy-go-lucky unpredictable personality’ (p. 11). Still little room for the Fantasy Fascist in the description of Law – Law is still described as usually the same as ‘good’ – but at least Chaos has expanded to find space for the heroic outlaw and the virtuous prankster.

In practice, and with half an eye towards the two-dimensional alignment system in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D), I try to strip the alignments of Law and Chaos of their connections with good and evil. I do my best to stress that these categories are something quite different. Believing that that it is virtuous to follow the rules, to stand for order, is independent of good or evil.

WFRP uses a system of five alignments; Law, Good, Neutral, Evil, and Chaos. Though it is suggested that the alignments are arranged in a linear order, the alignments are distinct. In the players section of the Hogshead 1st Edition rulebook, the alignments are described as ‘mostly self-explanatory – evil characters are basically evil and good characters are basically good. Chaos represents constant destruction and renewal, whereas Law represents a stasis of perfection in which nothing ever changes in the slightest degree, leaving Neutral characters as fairly free-minded and liberal beings, uncommitted to a particular frame of mind’ (p. 15). In the section for the Gamesmaster, these alignments are described in greater detail, with sets of ideas and attitudes that people of each alignment are ‘For’ and ‘Against’. Law, for example, is ‘for’ ‘rigid social hierarchy’, while Chaos is ‘against’ ‘permanence and tradition’. Here there is room for the Fantasy Fascist – indeed, one of the sister games of WFRP, Warhammer 40,000, is pretty much built on an idea of Space Fantasy Fascists vs The Universe – and this is complicated, and given further colour, by the fact that in the world of WFRP, Law and Chaos are ‘real’ things.

Law vs Chaos?

Unlike the D&D system, in which there is no ‘Big Bad’ built into the game, the drama of the Warhammer World is organised around the battle against Chaos. In the earliest WFRP material, it is clear that in the battle against Chaos, a victory for Law would be equally disastrous – it would be a victory for stasis, for the end of change, of progress, of invention, and imagination. But the victory of Chaos is inevitable – it is the entropic heat death of the Universe given demonic personality in the Chaos Gods of Tzeentch, Slaanesh, Nurgle, and Khorne [and Malal?]. Chaos is an essential feature of all change and progress in the Warhammer World, of all magic and invention, of pleasure, of ambition. And that is why it is so seductive. Evil is pretty petty and mundane – ordinary wickedness that does will neither undo the world nor be seen for other than what it is. But Chaos – change, progress, experimentation – is the world unwinding Big Bad, an essential feature of Human societies and their undoing. And it will, eventually, inevitably, unwind the world.

This ambivalent approach to alignment, and the fact that the concepts underpinning this system are integral, inseparable parts of the narrative of the game world, is what gives WFRP its distinctive colour. The colour of the D&D world – the Known World – comes despite a deliberately generic game system – from an exhaustive but piecemeal collection of supplements. Without the invention of the GM, those monsters in the sewers of Specularum are more often than not just another bunch of monsters. By contrast, those mutants in the sewers of Altdorf are, necessarily, the pitiable personification of the inevitable end of Humanity. And the witch-hunter who burns deformed babies? In the Black Eagle Barony he is a villainous agent of a tyrant. In the villages of the Reik he is fighting a battle against Chaos. Nobody said that Law was synonymous with goodness, or mercy. Indeed, the [impossible] triumph of Law, of stasis over entropy, would be as certain a defeat of Humanity as the victory of Chaos.

Labels:

Alignment,

Chaos,

DnD,

Dungeons and Dragons,

Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay,

WFRP

Tuesday 1 June 2010

Unstoppable Pincushions - HP in D&D

In D&D, characters steadily amass HP at each level, which means that a fifth-level character has, on average, five times as many HP as that character had at first level. Now, it doesn’t make that much sense to imagine that a fifth-level Magic User has acquired five times the capacity to have pointy bits of metal stuck in him. Without an injury system, the idea that each ‘hit’ scored in combat is an actual stab, slice, or bash with a club breaks the coherency of the fiction pretty quickly. Characters can quickly end up imagined as Saint Sebastian crossed with a Terminator.

Crivelli's Saint Sebastian says, "Is that all you've got? I'm a Paladin with 80 HP!"

If the concept of HP makes any sense, it is better to understand and, more importantly, to encourage players to conceive of them as ‘Hero Points’. Rather than the number of times the character can actually get hit, think of HP as the number of times the character can nearly get hit, can manoeuvre so as to take a glancing blow, can absorb sub-injury fatigue and bruising; the dead legs, the aching shoulders, the bruised ribs, the burning, gasping lungs, before a character takes a telling, fatal blow. Think of HP as a combination of fighting skill, experience, conditioning to the peculiar physical and psychological – e.g. dealing with stress, terror, and exhilaration – demands of combat, and perhaps most importantly luck and/or the blessings of fate. For human-sized characters at least, only a very small component of HP should be the ability to fight on with actual wounds. Because a human or demi-human ought to need only get stuck with a sword once before he dies, no matter the level, but then no ‘hero’ ought be killed by the first ‘hit’ in a role-playing game such as D&D.

Of course, the HP value of monsters need not represent exactly the same thing as it does for characters. HP is an abstract value. A Fighter’s 50 HP does not represent exactly the same thing as the 50 HP of a dragon. A dragon should be able to take many more actual sword blows than the human, in which case a greater proportion of the HP value is taken up by physical resilience, and less is derived from luck, fate, and that peculiar ability to make that last minute, but exhausting adjustments in the face of potentially lethal blows.

Narrating combat of this kind as a GM can be demanding. Draw on the choreography of the sword fights of cinema – characters arms grow heavy from constant parrying, the deflected blows of edged weapons still strike their victims, but on the flat, when weapons are locked the character with the upper hand is able to land a kick, a knee, a punch, or a headbutt, and characters scoring a 'hit' will have put their opponents in a series of awkward positions. And yes, a sub-lethal hit will sometimes be a nick or a graze. When done well this helps new players pick up on the level of abstraction found in most RPG mechanics – I have found that it breaks the coherence of the fiction for some new players when they are faced with the idea that they can ‘hit’ for maximum ‘damage’, but their opponent is able to fight on without any injury of significance to the game mechanics.

If the concept of HP makes any sense, it is better to understand and, more importantly, to encourage players to conceive of them as ‘Hero Points’. Rather than the number of times the character can actually get hit, think of HP as the number of times the character can nearly get hit, can manoeuvre so as to take a glancing blow, can absorb sub-injury fatigue and bruising; the dead legs, the aching shoulders, the bruised ribs, the burning, gasping lungs, before a character takes a telling, fatal blow. Think of HP as a combination of fighting skill, experience, conditioning to the peculiar physical and psychological – e.g. dealing with stress, terror, and exhilaration – demands of combat, and perhaps most importantly luck and/or the blessings of fate. For human-sized characters at least, only a very small component of HP should be the ability to fight on with actual wounds. Because a human or demi-human ought to need only get stuck with a sword once before he dies, no matter the level, but then no ‘hero’ ought be killed by the first ‘hit’ in a role-playing game such as D&D.

Of course, the HP value of monsters need not represent exactly the same thing as it does for characters. HP is an abstract value. A Fighter’s 50 HP does not represent exactly the same thing as the 50 HP of a dragon. A dragon should be able to take many more actual sword blows than the human, in which case a greater proportion of the HP value is taken up by physical resilience, and less is derived from luck, fate, and that peculiar ability to make that last minute, but exhausting adjustments in the face of potentially lethal blows.

Narrating combat of this kind as a GM can be demanding. Draw on the choreography of the sword fights of cinema – characters arms grow heavy from constant parrying, the deflected blows of edged weapons still strike their victims, but on the flat, when weapons are locked the character with the upper hand is able to land a kick, a knee, a punch, or a headbutt, and characters scoring a 'hit' will have put their opponents in a series of awkward positions. And yes, a sub-lethal hit will sometimes be a nick or a graze. When done well this helps new players pick up on the level of abstraction found in most RPG mechanics – I have found that it breaks the coherence of the fiction for some new players when they are faced with the idea that they can ‘hit’ for maximum ‘damage’, but their opponent is able to fight on without any injury of significance to the game mechanics.

Healing lost HP can present new narrative problems – if the physical aspect of HP are ‘sub-injury fatigue and bruising; the dead legs, the aching shoulders, the bruised ribs, the burning, gasping lungs’ etc., surely a simple rest will be enough to restore a character to full HP? Having played rugby as a front row forward – a sub-lethal level of physical confrontation – I know that this is a gross underestimation of the effects of a physical contest, even when they do not produce discrete, identifiable injuries such as sprained joints and broken bones. Sub-injury pain and fatigue can last for days. The biographies of professional rugby players talk of them having to be helped out of bed and into their clothes on the days after particularly brutal matches, and as for boxers… These are sub-lethal physical contests. Add in the psychological stress of engaging in deadly combat, and the concept of ‘using up’ luck, or the blessings of fate, and there is a good reason why it can take a character some time before they are back up to full HP after a particularly brutal fight – in game terms I allow recovery of 1 HP per Hit Dice(HD)/Level per day, with 1D3 HP per HD/Level per day if properly resting, and more if being nursed. Add in any narratively/mechanically significant injuries you might impose on the characters, perhaps when ‘hit’ within the range of their last HD, and you have a recipe for justifying why characters can’t simply bounce back to full HP after a good sleep, while at the same time maintaining that high HP characters aren’t being stuck with pointy bits of metal over and over again.

Labels:

Combat,

DnD,

Dungeons and Dragons,

Hit Points,

HP

Wednesday 26 May 2010

Known World, Old World

The Known World was my first fantasy role-play setting. A little continent of archetypal fantasy settings in the Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) Expert Rulebook (1983), with a short description of the setting in the accompanying module, The Isle of Dread, it was expanded in great detail throughout the 1980s, mainly by way of the superb Gazetteer series, until it became the world of Mystara. It is a high-fantasy setting with a light, humorous atmosphere. And it is a lot of fun if played that way.

The Old World is the world presented in the first edition of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay (WFRP) (1986). A faux-Renaissance Europe dominated by the Empire, corrupted from within by petty human failings and the shadow of Chaos, it was a setting richly detailed in the superb The Enemy Within campaign. It is a low-fantasy setting with a dark, humorous atmosphere. And it is a lot of fun if played that way.

In two imaginary worlds, and their associated game systems, we have neat encapsulations of the gulf between American and British pop-culture. One the one hand you have the Justice League of America, on the other the Justice Department of Megacity One. The Known World of D&D is bright, clean, and [super-]heroic. The PCs survive (mostly), save the world, defeat the evil, and grow powerful and rich. The Old World of WFRP is dark, dirty, and a grim struggle. If the PCs survive (and there’s a good chance they won’t), they merely forestall the spread of chaos, before they are permanently disabled fighting a pickpocket in a filthy alley, grow sick, and die in poverty.

And for a GM, or player, these two worlds and systems have, between them, all the rules and well-presented colour to run fantasy campaigns of whatever flavour you want. I have recently returned to roleplaying after a long period away – getting a degree, becoming a husband, getting a PhD, becoming a father, and breaking my body on the rugby fields of Yorkshire and South Wales. Those 15-20 years have given me a different perspective on what I want from a roleplaying game. This blog is about the Known World and the Old World, the game systems that they were built around, and my thoughts on playing these classic roleplaying games.

The Old World is the world presented in the first edition of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay (WFRP) (1986). A faux-Renaissance Europe dominated by the Empire, corrupted from within by petty human failings and the shadow of Chaos, it was a setting richly detailed in the superb The Enemy Within campaign. It is a low-fantasy setting with a dark, humorous atmosphere. And it is a lot of fun if played that way.

In two imaginary worlds, and their associated game systems, we have neat encapsulations of the gulf between American and British pop-culture. One the one hand you have the Justice League of America, on the other the Justice Department of Megacity One. The Known World of D&D is bright, clean, and [super-]heroic. The PCs survive (mostly), save the world, defeat the evil, and grow powerful and rich. The Old World of WFRP is dark, dirty, and a grim struggle. If the PCs survive (and there’s a good chance they won’t), they merely forestall the spread of chaos, before they are permanently disabled fighting a pickpocket in a filthy alley, grow sick, and die in poverty.

And for a GM, or player, these two worlds and systems have, between them, all the rules and well-presented colour to run fantasy campaigns of whatever flavour you want. I have recently returned to roleplaying after a long period away – getting a degree, becoming a husband, getting a PhD, becoming a father, and breaking my body on the rugby fields of Yorkshire and South Wales. Those 15-20 years have given me a different perspective on what I want from a roleplaying game. This blog is about the Known World and the Old World, the game systems that they were built around, and my thoughts on playing these classic roleplaying games.

Labels:

BECMI,

DnD,

Dungeons and Dragons,

Gazetteer,

Mystara,

Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay,

WFRP

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.png)